Nearly 99% of Autistic Adults Not Receiving Public Employment Services in the U.S.

- When Climate Disasters Hit, They Often Leave Long-term Health Care Access Shortages, Drexel Study Finds

- New Research Highlights Health Benefits of Using Heritage Art Practices in Art Therapy

- Chief Defender at the Defender Association of Philadelphia, Keisha Hudson, Will Address Drexel Kline School of Law Graduates at Commencement

- How an Experiential Learning Research Project Led to a Full-Time Job

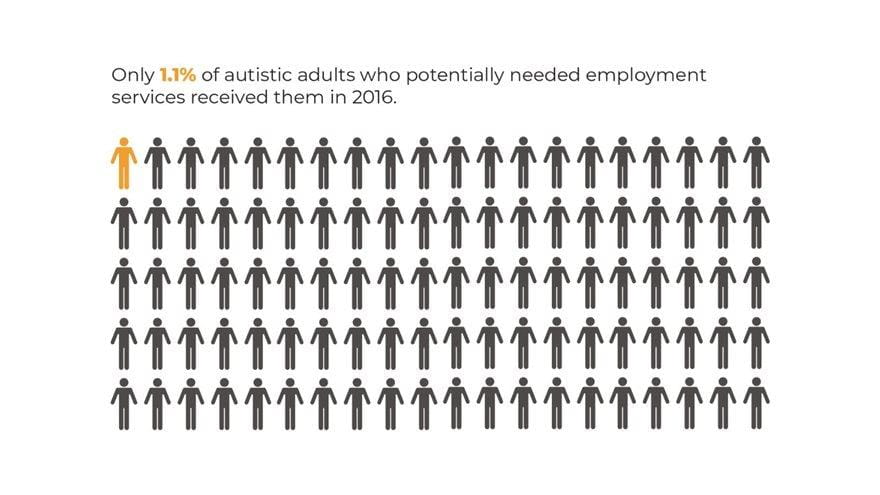

From 2008-16 an estimated 1.98 million autistic adults — or 99%, of those who likely needed employment services — did not receive support through Medicaid or Vocational Rehabilitation Administration, a new study from Drexel University’s A.J. Drexel Autism Institute finds.

Recently published in The Milbank Quarterly, the study reported on data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Department of Education’s Rehabilitation Services Administration. The researchers compared the distribution of employment services among autistic people to those with intellectual disability.

“Employment is a key social determinant of health and well-being for the estimated 5.4 million autistic adults in the United States – just as it is for citizens without disabilities,” said Anne Roux, a research scientist and director at the Policy Impact Project in the Autism Institute’s Policy and Analytics Center (PAC), who is lead author of the study.

Across both Vocational Rehabilitation and Medicaid programs, the research team estimated that only 1.1% of working-age autistic adults who potentially need employment services are actually receiving them. Only around 4,200 autistic people were receiving services through Medicaid waivers in 2016, while nearly 18,000 received Vocational Rehabilitation services.

There are stark contrasts between the two employment services’ offerings for autistic adults. Medicaid provides longer-term employment services for people with disabilities, while Vocational Rehabilitation provides short-term services. But between 2008-2016, Vocational Rehabilitation provided services for eight times as many autistic people as Medicaid did. The discrepancies were smaller among people with intellectual disability, who were three times more likely to receive services through Vocational Rehabilitation than Medicaid.

Medicaid funded employment services for fewer autistic people, but Medicaid’s spending on employment services among autistic adults were more than two times that of Vocational Rehabilitation’s spending.

However, across the timeframe, total spending on employment services among autistic adults decreased by almost 30% among Medicaid enrollees, but grew by nearly 400% among Vocational Rehabilitation service users.

“Public spending, as a whole, is going toward short-term employment services, even though many autistic people are likely to need some level of flexible, longer-term supports across the working years,” said Roux.

The research team was surprised by the gaps in the capacity to provide public employment services.

“It is difficult for me to wrap my brain around exactly how few people are receiving public employment services,” said Roux.

Roux added that autistic people are not guaranteed access to services to support functioning and wellbeing after they leave high school. Once special education services end, there exists what is known as a “services cliff” — a gap in service eligibility — because there is no federal law that enables autistic adults to continue to receive the services and support they may need for the rest of their lives. The services cliff is compounded by severely limited access to employment services. Even when services are available, the road to getting services is often very difficult to navigate which prevents people from achieving their potential, and traps people in a life of forced poverty and increased health care costs.

The research team was attempting to investigate the bigger picture of how employment services for autistic adults are funded in the U.S. But, they noted, there isn’t public access to data that captures employment services for autistic people across the Medicaid and Vocational Rehabilitation systems.

“Therefore, the astounding gaps in our capacity to provide these public services are usually only noted in the stories of people who repeatedly tell us they cannot access the help they need or the people looking to bolster delivery of these services,” said Lindsay Shea, DrPH, leader of PAC and the primary investigator on this research. “These findings speak truth to those experiences and why funding for these services is critical.”

Because of this, the research team suggests there is a dire need for policy changes to improve the employment services systems in the U.S.

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreements UJ2MC31073 and UT6MC45902 Autism Transitions Research Project. The information, content, and/or conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.