When the World Changes, Drexel Changes With It

- Drexel’s College of Nursing and Health Professions Receives $1 Million for Scholarships from the Bedford Falls Foundation – DAF to Address Nursing Workforce Shortage

- Laura Turner to Join Drexel University as Senior Vice President for Institutional Advancement

- U.S. Department of Education Provides Final Approval of Drexel and Salus Merger

- Questions About the Drexel-Salus Merger?

Drexel University was originally contained in this one building, Main Building at 3141 Chestnut St., when it was founded in 1891. The black-and-white photo was taken in 1900 (photo courtesy the Library of Congress) and the colorized photo was shot 125 years later in 2025.

“I know the world is going to change, and therefore, the university must change with it.”

That updated quote is attributed to Drexel University’s founder, the Philadelphia-born financier and philanthropist Anthony J. Drexel. Across three centuries, Drexel has continuously reinvented itself to meet society’s needs and prepare students for the future, all while remaining true to both its founder and its founding vision. Today’s University would likely be mostly unrecognizable — in a good way! — to Anthony, who died less than three years after the original Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry opened in 1891.

About 134 years later, the University has just completed a yearslong integration with the former Salus University and will continue to transform under the vision and guidance of a new president who started this month. It’s a time of transition that future Dragons could look back at as a major turning point.

But what were some of those other major changes that brought Drexel to where it is today?

1914: Degrees, Not Diplomas

The Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry initially focused on training the workforce and offered vocational courses on a class-by-class basis or towards a diploma (less time-intensive, laborious and prestigious than a degree, and in some cases valued more for trades). While its Board of Trustees noted that “the Drexel Institute could not be placed in the position of granting degrees to its graduates unless there were radical changes, especially as to the lengths of courses of instruction” back in 1905, it took another nine years, and a new president, to implement this.

Hollis Godfrey, PhD, an administrator, writer and engineering consultant, was originally hired to survey the institution before he was invited to be its president. Serving from 1913 to 1921, he simplified and modernized the institution in major ways that can still be seen more than a century later.

Godfrey organized Drexel’s 18 independent departments into three schools: the School of Engineering, the Secretarial School and the School of Domestic Science and Arts. He also standardized curricula into two- and four-year programs, which led the way for accreditation to grant degrees at a time when a college degree was beginning to open more professional opportunities.

In 1914, Drexel granted its first degree, a Bachelor of Science in engineering; three years later, its offerings expanded to include a B.S. in secretarial work and a B.S. in domestic science and arts. Today, the University offers more than 200 undergraduate degrees and graduate degrees (not to mention minors and dual degrees).

1919: Creating Co-op

Godfrey’s other legacy was the creation of Drexel’s co-operative (co-op) education program, which is one of the University’s most unique and most utilized offerings.

Outside of academia, Godfrey was revered as a technology and warfare intellectual: He wrote the 1908 bestselling science fiction novel “The Man Who Ended War” and co-created the Council of National Defense emergency government agency as part of his noted involvement in the war effort during World War I (which started and ended during his Drexel presidency). When male students dropped out to enlist, Godfrey advocated for them to stay enrolled to learn technical training rather than be thrown into the trenches — something that could be done in partnership with the military and the government.

The cooperative education model of balancing academics with professional work experience had been founded in 1906 at the University of Cincinnati, but Drexel still became an early adapter. Just a handful of years after shifting to grant degrees, the institution adjusted its curricula, plans of study and academic calendars; began enrolling a new type of student and created partnerships with co-op employers.

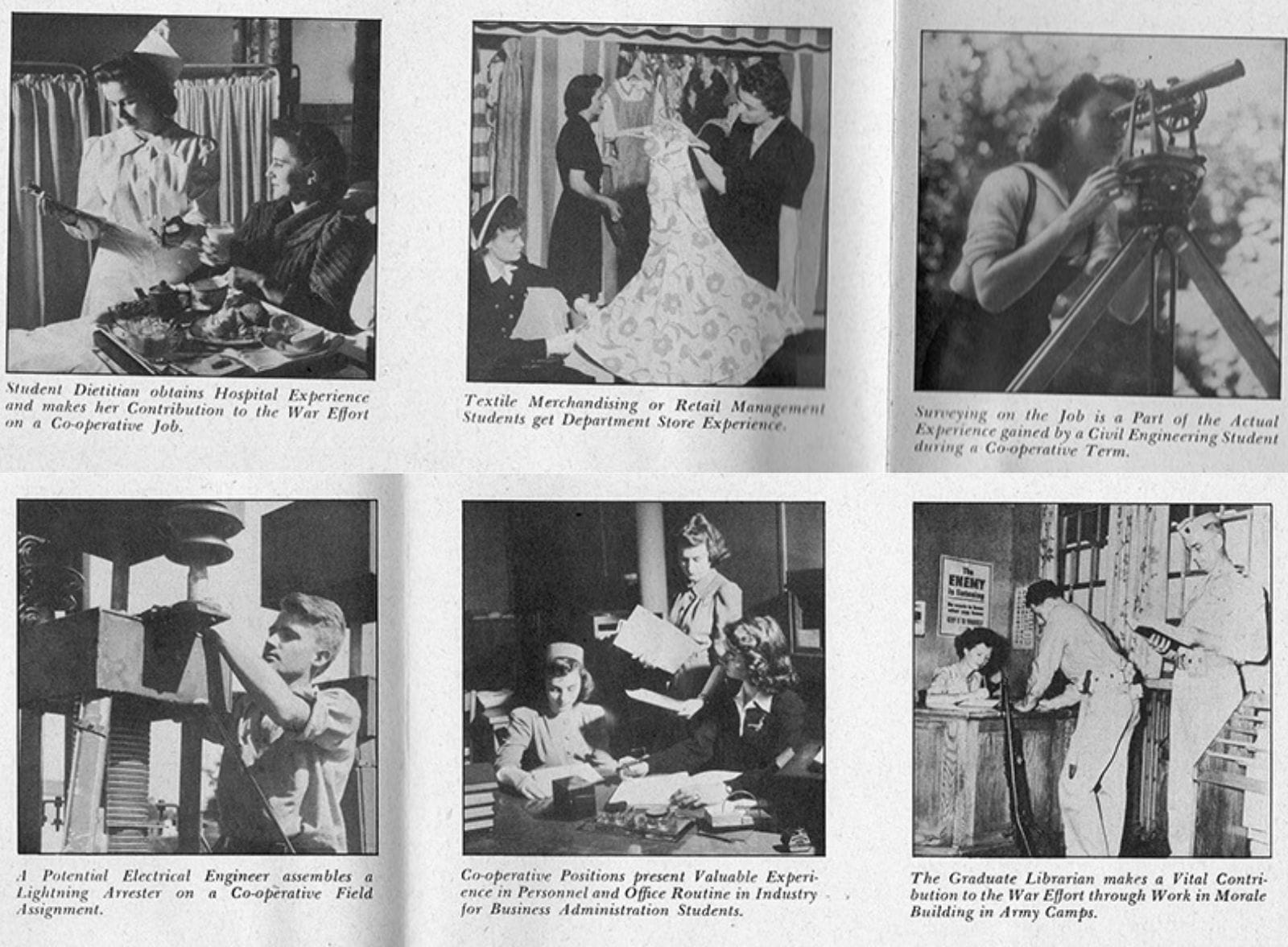

Drexel’s co-op program was first offered in 1919 as part of a four-year plan for mechanical engineering, electrical engineering and civil engineering students. In its early years, co-op expanded to include other disciplines and offer a five-year co-op plan as well.

At the time of its centennial anniversary in 2019, the Drexel Co-op had grown from 152 engineering students placed at five local companies to over 5,300 students from all majors working at over 1,500 employers in 38 countries and 31 states.

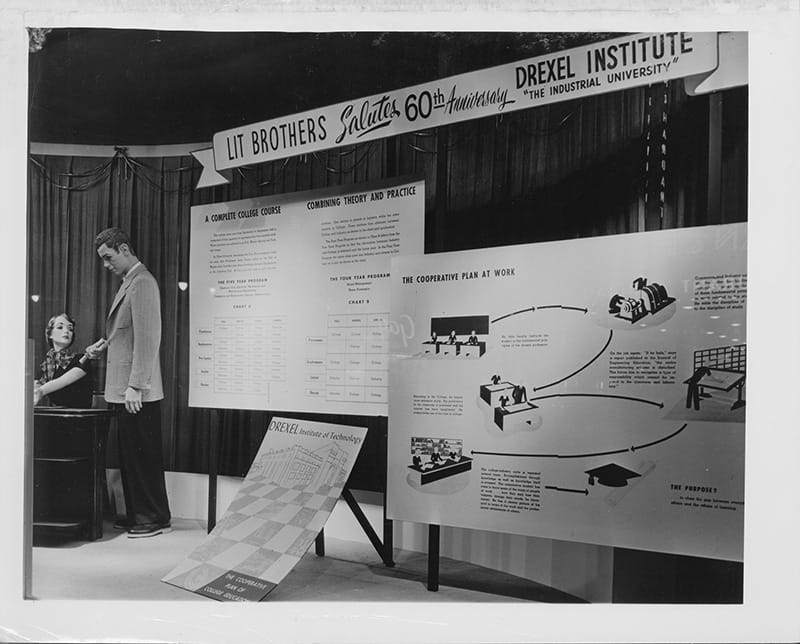

1936: The First Name Change

The “Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry” name was no longer accurate after the fine and applied arts programs shut down in 1905 after failing to distinguish itself both internally and externally. As a result, the institution became more “science” and “industry” than “art,” though it still maintained its founding art collection and art gallery.

As soon as the former Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn president Parke R. Kolbe became Drexel’s fourth president in 1932, he was asked by the Drexel community to change the institute’s name — a fitting request of a trained linguist and former professor of modern languages. The switch to the “Drexel Institute of Technology” was approved in 1936, by which time Drexel offered B.S. degrees in civil, electrical, mechanical and chemical engineering as well as home economics, commerce, secretarial studies and library science. The change in focus, reflected in the new name, benefited the University during and after World War II, which also fundamentally changed Drexel’s academic, research and co-op programs (particularly in engineering) and bolstered relationships with the government and industry partners.

1970: The Second Name Change

Under the post-war presidency of James Creese from 1945–1963, Drexel greatly expanded its enrollment, budget and campus size. Creese’s successor was Drexel’s longest-serving president, William W. Hagerty (1963–1984), who used that solid footing to create a fully realized university that could offer graduate degrees as well as a liberal arts education. After he initiated the transition in 1968, another name change was approved by the Drexel community two years later for the new “Drexel University.”

The new name reflected academic, structural and cultural changes. Drexel awarded its first PhD (in mechanical engineering) in 1967 to Richard Mortimer, who was then hired as part of the growing number of Drexel faculty with PhDs (which rose from 24 to 94 percent during Hagerty’s tenure). And while Creese had incorporated the humanities through a “Reading in Industry” program, Hagerty replaced it with a new B.S. in humanities and science in the mid-1960s and, later, the creation of an entire College of Humanities and Social Sciences in 1969. Becoming a university helped Drexel grow its research enterprise to be recognized as a prestigious R1 research university in 2018, by which time the University had added three schools in health sciences as well as a law school.

1984: A Historic Computer “First”

By the end of Hagerty’s presidency, enrollment had been decreasing at a Drexel already facing financial difficulties from national, federal and local challenges. But its finances improved and the University enrolled its largest class ever in 1984 after a yearslong, University-wide coordinated effort to make Drexel the first university in the country to require students to have access to a personal microcomputer.

In preparation, the University provided training and computers for all faculty to adapt their courses and teach computer literate students. Drexel partnered with the burgeoning Apple Computer, Inc. (today’s Apple Inc.) to offer Dragons the innovative Apple Macintosh personal computer at a discount before it was available to the public. The transformation led to Drexel’s national reputation as a technological innovator, and a generation of Drexel students entering the co-op and post-graduation workforce with much more computer experience than their peers.

2002: New Offerings, New Schools

More than 110 years after its founding as a vocational school, Drexel began offering health and medical education for the first time. Under the dynamic presidency of Constantine Papadakis (1995–2009), Drexel assumed management of the closing MCP Hahnemann University’s academic schools and colleges in 2002 — today’s College of Nursing and Health Professions, College of Medicine and Dana and Dornsife School of Public Health. With these schools, Drexel also acquired its Queen Lane Campus in East Falls and Center City Campus in Philadelphia.

MCP Hahnemann University’s teaching hospital became Drexel’s primary teaching hospital — Hahnemann University Hospital — until its parent company filed for bankruptcy and closed the hospital in 2019. Drexel subsequently entered an academic affiliation with Tower Health, jointly purchasing the St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children (from the same owner as Hahnemann University Hospital) for the University and building Drexel’s West Reading Campus for medical students next to Tower Health’s Reading Hospital. Since then, Drexel has grown its educational offerings, research capabilities, teaching sites, partner affiliations and post-graduation opportunities — which partly impacted Drexel’s acquisition of another university two decades later (more on that below).

The Ecology of Fashion, the first-ever co-created exhibition with Drexel’s Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts and Design, is on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences through August. Photo credit: Ramon Torres, Academy of Natural Sciences.

2011: Drexel Acquires a Museum

After two centuries as a prestigious organization and museum, the Academy of Natural Sciences entered an affiliation with Drexel, a longstanding partner, that changed both institutions. The oldest natural sciences institution in the Western Hemisphere became part of Drexel about a year into the presidency of John Fry (2010–2024). As a result, Drexel’s College of Arts and Sciences created the Department of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science (BEES) that incorporated the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University and its collections into co-op, research, courses, teaching, outreach and field site projects. Non-BEES Dragons have also benefited from and undertaken those same projects, and all students, faculty and professional staff can gain free admission to the museum with their DragonCards.

Later, when Philadelphia’s city history museum, the Atwater Kent, closed to the public in 2018, Drexel contracted with the City of Philadelphia to evaluate and steward the historical collections of the shuttered museum. This led to a broader effort to centralize the care of all of Drexel’s collections, from the Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections (detailing the history of the College of Medicine and its predecessor institutions) to the vast collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences to the Drexel Founding Collection of University art (first established by Anthony J. Drexel himself).

2020: COVID-19’s Impact

A full five years — and a whole generation of students — after the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020, there are practices, technologies, programs and other projects still used today that would not have existed without Drexel’s pandemic pivot.

With campus closed for more than a year, Drexel students, faculty and professional staff adapted their teaching and learning, co-ops, student organizations, civic engagement, external partnerships and more — and some of those changes can still be seen today. Dragons in nursing, public health and medical fields came together as part of Drexel’s COVID-19 response to build and oversee test centers and vaccination clinics and build a testing lab that is now Drexel Medicine Diagnostics. Zoom and virtual classes have now entered the University’s status quo for faculty, professional staff and students.

2025: A Three-Pronged Transition

Drexel recently completed its acquisition of the former Salus University, whose healthcare programs are now part of the College of Nursing and Health Professions and the College of Medicine. Salus’ preexisting Pennsylvania College of Optometry became Drexel’s newest college, and the Elkins Park Campus its newest campus location. Now, the University has even more medical education opportunities to offer on its roster that’s expanded in the last 25 years.

The Drexel-Salus merger was first announced in 2023, about a year into Drexel’s yearslong Academic Transformation initiative to combine several Drexel schools and colleges, transition to a semester calendar, redesign curriculum and standardize practices and policies across academic units. With those planned changes formally approved this year, Academic Transformation is expected to be finalized in the next academic year and will be completed by August 2027.

While both Academic Transformation and the Salus integration were started during the Fry era, they will be completed and enacted during the presidency of Antonio Merlo, PhD, who became Drexel’s 16th president on July 1. Throughout the University’s three centuries, many transformations were enacted through the visions of the Drexel president at the time, and Merlo can do the same with his leadership.

What will come next at Drexel? Only time, and Dragons, will tell.

In This Article

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.